Capturing the Leafs fandom on film

Documentary maker Dale Morrisey was filming outside Scotiabank Arena to capture Legends Row, statues of Toronto Maple Leafs players, including Syl Apps, Johnny Bower and Darryl Sittler.

Documentary maker Dale Morrisey was filming outside Scotiabank Arena to capture Legends Row, statues of Toronto Maple Leafs players, including Syl Apps, Johnny Bower and Darryl Sittler.

A family of immigrants watched him work and then asked if he could take their picture. “Of course, I can. Where are you from and what brought you to the arena?” Morrisey asked.

“We’re from Afghanistan and we came here a year ago,” the mother said. “We want to be Canadian – so we want to cheer for the Leafs because that’s what you do.”

For Morrisey, that sums up the theme of Being Leafs Nation, his latest documentary series. It’s the story not just of a hockey team and its obsessive fans, but of Canada itself. While many in Kingston align themselves with Boston, Montreal or Ottawa, there is no question that the Leafs have had a huge impact on hockey and the country.

“In many ways, they are Canada’s team,” he argues.

Ever the storyteller, the Bath-based filmmaker switches gears to talk about the role hockey served in shoring up the morale of Canadians serving overseas during the Second World War. There was no television yet and Foster Hewitt’s Hockey Night in Canada radio broadcasts didn’t reach overseas. Instead, the military recorded them on 78 rpm records and shipped them to the troops in Europe. The service men and women would gather to listen – the game had been played weeks earlier and the record only captured one or two periods, but it connected them with home. They loved hearing Hewitt yell: “He shoots, he scores!”

With Being Leafs Nation, Morrisey started out to make a single hour-long documentary. However, he ended up with almost 70 hours of interviews with players like Kingston’s Doug Gilmour and Rick Vaive, as well as superfans who have turned their rec rooms into blue and white shrines. With so much content, he divided the history into three periods.

In the first episode, he covers the beginning of the team under the legendary Conn Smythe and the growth in popularity of the team thanks to Hewitt’s broadcasts. Period two, the Glory Years, highlights Bill Barilko’s famous Stanley Cup winning goal in 1951 and the team’s dynasty in the 1960s, which saw it win four Stanley Cups.

Period three is called the Circus Comes to Town and deals with the dark period of ownership under Harold Ballard. However, it finishes on a more positive note, looking at the team’s resurgence in recent years.

Morrisey has been creating hockey documentaries for many years. It all started in the 1990s at the former International Hockey Hall of Fame building beside Kingston’s Memorial Centre, where Morrisey had a part-time job as a curator. As a Loyalist College journalism student, he had to produce a short documentary for a class – and put one together about the Hall.

“It was terrible,” he says with a laugh. Nevertheless, the film caught the eye of Hall historian Bill Fitsell, who told Morrisey: “You should switch from museum work to story-telling. You will be poor either way, but you’ll have more fun.”

Morrisey went on to create The Father of Hockey, a documentary about Capt. James Sutherland, the founder of the Memorial Cup and the driving force to establish the Hockey Hall of Fame in the 1940s. His contribution to hockey was huge. Sutherland wanted to establish the Hall in his hometown of Kingston – but there were two problems.

First, his claim that Kingston was the site of the first organized hockey game in 1886 between Queen’s and RMC wasn’t true. Matches had been played in Montreal since 1875.

Secondly, Sutherland was up against Conn Smythe. Like many Torontonians, Smythe thought the city was the centre of the universe and was determined to locate the Hall there. “The double crosses and backstabbing were incredible,” says Morrisey. “The fix was in early on that Kingston was not going to get the Hockey Hall of Fame.”

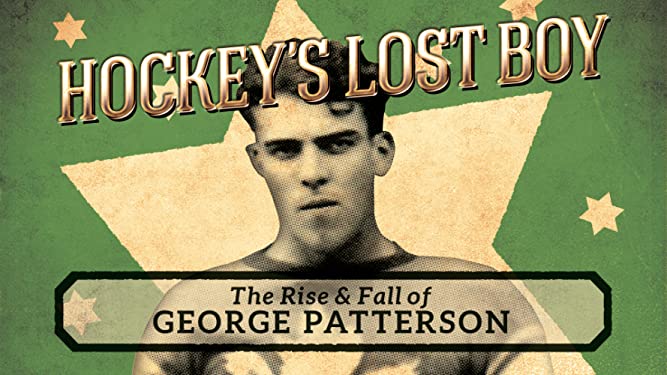

Another Morrisey film, Hockey’s Lost Boy, told the story of the founding of the Maple Leafs and of Kingston’s George Patterson, who scored the team’s first goal on Feb. 17, 1927. Yes, that initial goal was in the middle of the season.

Another Morrisey film, Hockey’s Lost Boy, told the story of the founding of the Maple Leafs and of Kingston’s George Patterson, who scored the team’s first goal on Feb. 17, 1927. Yes, that initial goal was in the middle of the season.

Today, an organization making a huge brand shift will plan it for months in advance.

In 1927 the Irish-green squad, the St. Pats, was suffering both financially and on the ice. When Conn Smythe took over the team in February, he immediately decided to rename the team the Toronto Maple Leafs.

The brand change happened so quickly that the Leafs weren’t wearing their now famous blue and white sweaters that night. “In the minutes leading up to the game, the equipment manager was still stitching the Leafs logo onto the green sweaters,” Morrisey laughs.

As for Patterson, he has been long forgotten. “In their official history, the Leafs don’t even mention him,” Morrisey says. “He was in the dustbin of history – at best, he was a trivia question.” Morrisey made the Patterson documentary because he wanted him to get the recognition he deserved.

Being Leafs Nation will be broadcast in the fall on several PBS stations along the Canadian border, including Watertown and Buffalo. Morrisey says Canadian networks like CBC and TVO did not show any interest in the project. On the other hand, PBS, with its legions of viewers in southern Ontario, snapped it up quickly. While PBS does not carry advertisements, Morrisey is still looking for sponsors for Being Leafs Nation.

For Morrisey, these documentaries are a labour of love, one that was sparked when he was a boy watching Hockey Night in Canada with his dad. He was only allowed to stay up for the first period. Then he would hide his radio in his bed and listen to the second period before falling asleep. The next morning, he would run downstairs to ask his father: “Who won the game? Who won the game?”