Willie O'Ree was the first black player in the NHL

Willie O’Ree didn’t set out to be the first black player in the NHL. He was just determined to play in the league – period.

When he stepped onto the ice at the storied Montreal Forum in a Boston Bruins uniform on Jan. 18, 1958, O’Ree’s family and friends were in attendance for the momentous occasion. The Hockey Night in Canada broadcast didn’t mention it, nor did the local media.

“It didn’t really register with me,” O’Ree said in an interview with the Original Hockey Hall of Fame. “I was just so excited to be playing in an NHL game.”

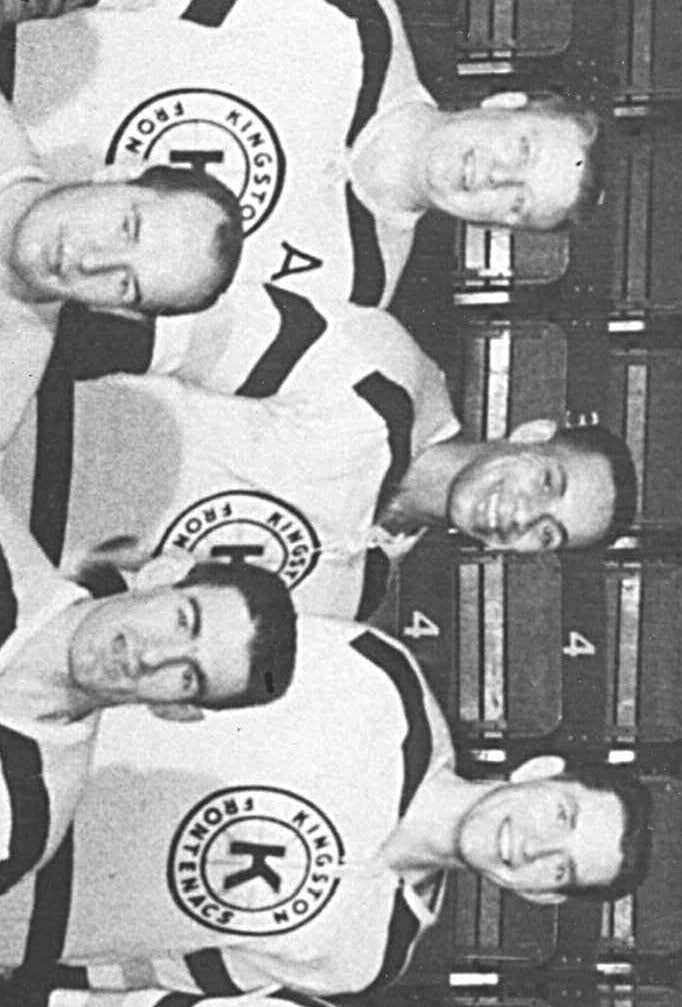

After playing just two games with Boston, O’Ree skated in 1959-60 with the Kingston Frontenacs of the Eastern Professional Hockey League. He had an outstanding season, notching 46 points in 50 games.

O’Ree acknowledges that he should not have been the first black player in the NHL. While Jackie Robinson had broken the colour barrier in baseball in 1947, it seemed that hockey was not quite ready to do so. One particular player, Herb Carnegie, was a star in the Quebec Senior Hockey League, having been named league MVP in 1946, 1947 and 1949. While fellow Quebec league players like Jean Beliveau went on to wondrous NHL careers, Carnegie was stuck in the minors.

Racism was pervasive among NHL owners and managers. In addition, teams were worried about alienating their mostly white fan base by adding black players.

“Herbie should have been there – he had all the skills and talent to be in the NHL,” O’Ree says.

Over his 24-year career in the NHL and minor leagues, O’Ree constantly endured racist taunts from opposing players and fans. He ignored them.

Race even entered into his personal life. While in Kingston, he began dating a young white woman who worked in the business office at Queen’s University. It was his first serious relationship. However, his parents were opposed – believing that mixed-race dating would make O’Ree a target.

“My parents were very strict on dating within our own race. They were worried things would happen so I had to break it off.”

The Kingston Frontenacs had two black players – O’Ree from New Brunswick and Stan Maxwell from Nova Scotia – which was unusual at the time. They had played together in the Quebec league and O’Ree was happy to be reunited with him.

“It was great to be back there with my good friend Stan, who always had my back, just as I had his,” O’Ree says. “It wasn’t because we were both black, either; it was more that we’d both come from large maritime families and knew how lucky we were to be there.”

Maxwell had two outstanding seasons in Kingston, notching 73 points the first year and 58 in the second. However, he never got the call to play in the NHL.

O’Ree enjoyed his time in Kingston and says he was respected by teammates and local fans.

“He was a hell of a hockey player,” recalled the late Len Coyle, a fan at the time who would go on to serve as equipment manager with the Kingston Canadians and Frontenacs. Coyle didn’t remember any incidents of racism in Kingston.

“You wouldn’t have that around here,” Coyle said. “A lot of people liked him.”

The late hockey historian Bill Fitsell remembered O’Ree as an unassuming team player. “He wasn’t a star but he was a good, useful forward.”

Kingston proved to be the launchpad for O’Ree’s return to the NHL. With his stellar season in Kingston, he earned another opportunity with the Bruins. He went on to play 43 games with Boston in the 1960-61 season. He wasn’t a prolific goal scorer, but did collect four goals and 10 assists.

And he did it all with only one eye. It was the biggest secret of his life – for he knew he wouldn’t be allowed to play in the NHL if coaches discovered that he was partially blind.

When he was hit in the eye by a puck at the age of 19, doctors told him that he would never play again. He secretly set out to prove them wrong. “I said to myself: ‘Willie you can do anything you set your mind to.”

At first, he had trouble following the puck and seeing the opposing players coming in for a check. Then he had an epiphany. “I decided to forget about what I can’t do and concentrated on what I could see.”

Somehow it worked. And he managed to keep his eye troubles secret throughout his hockey career.

Somehow it worked. And he managed to keep his eye troubles secret throughout his hockey career.

After his solid but unspectacular 1960-61 season with the Bruins, O’Ree moved to the minors. He had a 24-year run, mostly in the Western Hockey League, capturing two scoring titles before retiring in 1980.

After hanging up his skates, he worked in security for a hotel in San Diego. In 1998, the NHL came calling, inviting him to become diversity ambassador, spreading the word about the game to boys and girls across North America.

Now called the Hockey for Everyone program, it sees O’Ree and others traveling to spread the message of inclusion and giving kids an opportunity to try the sport. Then the pandemic hit. O’Ree was ordered to stay home and stay safe.

At the age of 85, O’Ree is itching to get back on the road when covid eases. “Whether they go on to play in college or as adults, the goal is to teach young people. It’s all about goal setting and believing in yourself.” He receives regular emails from youth who participated a decade ago, talking about the huge difference it made in their lives.

Asked to name his hockey highlight, he has trouble coming up with just one. That night at the Montreal Forum in 1958. Scoring his first NHL goal, on Jan. 1, 1961 (once again vs. Montreal). Being named to the Order of Canada. His induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a builder in 2018 (at the same time as Kingston star Jayna Hefford). And the Bruins’ plan to retire his number, 22, at a ceremony next February.

“I feel that I’ve been blessed over the years,” he says.